This page is a comprehensive resource and serves as a repository of research articles, reports, policy briefs, toolkits, and multimedia content, all centered around promoting sexual and reproductive health, gender equality, and human rights 📚

Titled The Real Fertility Crisis – The Pursuit of Reproductive Agency in a Changing World, this year’s State of World…

This new study was commissioned by Members of the European Parliament, Saskia Bricmont, Mélissa Camara and Diana Riba I Giner,…

Ever noticed your sex drive doing its own thing during your cycle? That’s your hormones – estrogen and progesterone –…

This guide consolidates practical insights, lessons, and methodologies on knowledge brokering in development cooperation. We intend for this guide to…

Today, we close the 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-Based Violence on a powerful note: Human Rights Day. This annual…

As we work toward eliminating gender-based violence, it is essential to reflect on the foundations of our progress. With the…

Written by Shannon Mathew, SN-NL Knowledge Management Expert Over the past two weeks of the 16 Days of Activism Campaign,…

Human trafficking is a grave human rights violation that affects millions of people of all ages and from all backgrounds…

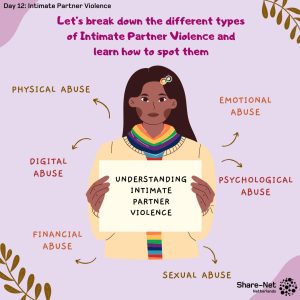

Written by Nicole Moran, SN-NL coordinator and Birth Doula Intimate Partner Violence and Its Many Faces Intimate Partner Violence (IPV)…

Written by Amie Kherame Ndong, Knowledge Expert and Knowledge Activation Grants Lead at Share-Net International and SRHR Advisor at KIT…

This post uses “transgender” and/or “trans” as umbrella terms to encompass various forms of gender nonconformity. I recognize that not…

Disability Justice and Sexual and Gender-Based Violence By Marieke van Gerwen, SRHR Advisor and Daphne Visser Advocacy and SRHR Advisor…